Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

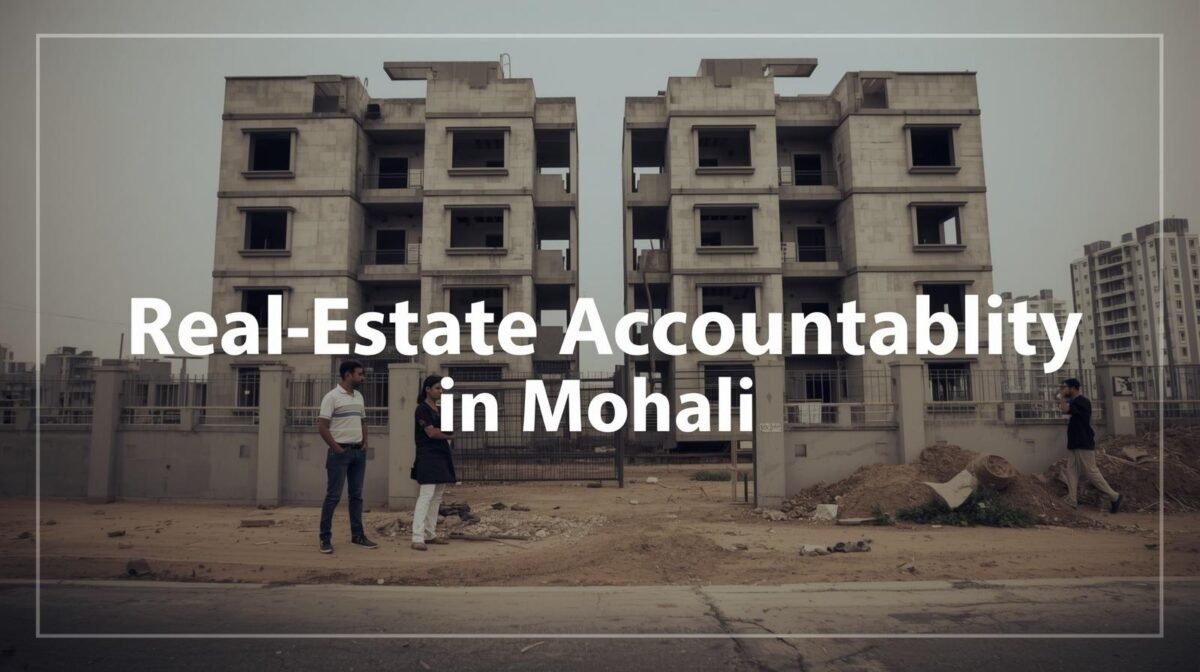

The promise of stronger consumer protection in Punjab’s property sector is being tested as buyers across Mohali and Panchkula face mounting delays, legal hurdles, and limited recourse. Despite a decade of rapid growth in the region’s housing market, residents say real estate accountability in Mohali remains elusive.

When the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act was introduced in 2016, it was meant to create a level playing field by forcing transparency on developers and safeguarding buyers. Punjab and Haryana both set up Real Estate Regulatory Authorities with a mandate to ensure projects were approved only after due diligence, to enforce delivery timelines, and to resolve disputes within 60 days. Yet, nearly a decade later, the reality on the ground is different.

One of the most prominent failures involves Gupta Builders and Promoters, once considered a key player in the region. The company left India in 2022, abandoning more than 2,500 investors. Its projects in Kharar and Zirakpur, including Camelia and GBP Centrum, have remained unfinished since 2016. Buyers allege they were assured that RERA would cancel the builder’s license and hand control of construction to allottees. Three years on, however, no transfer has taken place. The Enforcement Directorate has since attached company assets, but families who put their savings into flats remain without possession.

Officials at Punjab RERA declined to comment on the specifics of the case. However, homebuyer associations argue that such silence underscores a deeper structural weakness. The regulator receives hundreds of complaints every year, yet penalties imposed on developers often go unpaid, and enforcement orders are rarely acted upon.

The backlog is significant. GMADA, the Greater Mohali Area Development Authority, is handling more than 500 unresolved complaints as of June 2025, most relating to delayed possession and inadequate infrastructure. Punjab RERA has nearly 1,000 pending complaints, 70% of them originating from Mohali district. The Haryana Shehri Vikas Pradhikaran, responsible for Panchkula, is grappling with over 300 unresolved cases. Staff shortages and administrative delays are cited as reasons for the mounting pendency, but buyers point to a more systemic issue: pressure from politically connected builders.

Residents who attempt to hold developers accountable describe a cycle of frustration. Builder-buyer agreements often include harsh penalties for late payments by customers, yet offer little in return when projects stall for years. Consumers say they must navigate lengthy complaint procedures, high legal costs, and inconsistent rulings. Even when they win favorable judgments, enforcement is slow or absent.

Not all outcomes are bleak. Earlier this year, the State Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission intervened in a case involving TDI City, a township in Mohali’s Sectors 110 and 111. After years of delays, the commission ordered the deputy commissioner to attach the project and directed the developer to refund buyers. Following the order, possessions were finally handed over. While the case demonstrated that remedies are possible, experts note it required extraordinary legal action, rather than the routine functioning of regulatory systems.

Industry observers argue that reform is overdue. Advocates suggest strengthening the enforcement powers of RERA to ensure that penalties bite and orders cannot be ignored. Digitising complaint systems and publishing monthly reports on pending cases could enhance transparency. Others stress the importance of collective action. Organised resident groups are more likely to draw attention to their grievances, while media coverage often exerts pressure that official channels do not.

For many in the market, however, trust has already eroded. Homebuyers say they now approach new projects with suspicion, scrutinising approvals more closely and demanding evidence of financial stability from developers. Lawyers recommend that allottees verify builder credentials and confirm project registrations before committing funds.

Regulators acknowledge the gap between expectations and delivery. A senior GMADA official admitted that accountability systems exist largely on paper, with limited enforcement in practice. Officials in Panchkula offered similar assessments, noting that bureaucratic complexity often discourages residents from filing complaints.

The stakes extend beyond individual buyers. Mohali has become one of Punjab’s fastest-growing real estate hubs, attracting investment not only from local families but also from non-resident Indians. If the perception of weak enforcement persists, experts warn it could dampen demand and slow down what has been one of the region’s most dynamic markets.

Real estate accountability in Mohali has therefore become more than just a consumer issue. It is a test of whether state institutions can balance rapid development with fairness, transparency, and rule of law. Without reform, the risk is that residents will continue to bear the cost of unfinished projects, while confidence in the regulatory framework diminishes further.

Accountability refers to builders meeting timelines, regulators enforcing laws, and buyers receiving promised projects without delays.

Delays are linked to financial mismanagement by builders, staff shortages in regulatory bodies, and political interference in enforcement.

Punjab RERA has resolved some cases, but with nearly 1,000 complaints pending, enforcement and penalty collection remain weak.

Buyers can approach RERA, consumer courts, or form associations to collectively pursue cases. Some also seek relief through state commissions.

Experts advise verifying builder credentials, confirming RERA registration, and reviewing agreement terms carefully before committing funds.